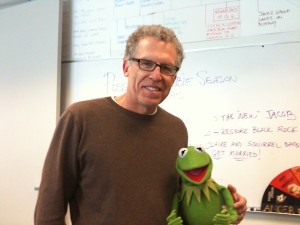

Having worked with Elmore Leonard for 30 years, I’ve developed a special appreciation for writers and an understanding of what they go through to bring their stories to life. I first met Carlton Cuse through Elmore Leonard, as Carlton was both a big fan of Elmore’s work and later collaborated with Elmore and director John Dahl on an adaptation of one of Elmore’s books, “Riding The Rap.” Through this experience Carlton and I became friends. This interview with Carlton is the first in a series of interviews with writers whose work I admire — getting them to share stories about their lives and their writing process that I hope will be both illuminating and entertaining.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Carlton Cuse was born in Mexico City on March 22, 1959. His father was American, working in Mexico for his grandfather, who had a machine tool manufacturing business. After a few years in Mexico City his parents moved to Boston, where as a boy he instantly bonded with the Boston Red Sox and began a lifelong love for the team.

A few years after moving to Boston, his dad took a new job and the Cuse family moved to Tustin, California. His parents were divorced shortly thereafter, and his mother raised Carlton and his brother.

Carlton went off to boarding school in 10th grade to The Putney School in Putney, Vermont. The school was on a working dairy farm, and it placed a strong emphasis on an education in the arts, music and the outdoors.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Gregg: When did you realize you wanted to be a writer?

Carlton: It was at Putney School. In that environment my desire to become a writer really blossomed. I did a lot of creative writing for classes. And I devoured the works of authors like John Steinbeck, Kurt Vonnegut, Elmore Leonard and Stephen King. I always had all these story ideas running though my head, but back then I wasn’t quite sure what to do them.

Gregg: For an aspiring writer, why’d you pick Harvard?

Carlton: After growing up in suburban southern California, then going to boarding school in rural Vermont, I really wanted to go to college in an urban environment. I knew Harvard was an amazing school with a lot of different offerings.

Gregg: How’d you get involved with rowing?

Carlton: Once I got to Harvard I was plucked out of freshmen registration by the freshman crew coach who said, “Hey, have you ever thought about rowing? I underwent this transformation from being an outdoors guy to being a hardcore athlete as an oarsman and member of the Harvard crew.

Gregg: What were your academic goals in college?

Carlton: My original plan was to go to medical school because we had all these doctors in my family. But the truth was I hated my pre-med courses. My uncle who was a surgeon tried to get me psyched up by inviting me to scrub in for a surgery, but as he was opening up the patient and cauterizing capillaries and as the air filled up with the smell of burning human flesh, I fainted. So that pretty much scratched my plan to go to medical school. Instead I followed my heart and majored in American History. I was drawn to the history department because I loved reading biographies and historical narrative. And there were some amazing professors who really brought history to life.

Gregg: So how did you go from history at Harvard to pursuing a career in film?

Carlton: Somewhere around my junior year I had a chance meeting with the filmmakers of the Paramount film, Airplane. They were at Harvard to organize a test screening, and wanted to record the audience reaction to get a sense of how to time the final cut of the jokes in the movie. I helped organize the screening. The process was fascinating; the movie was hilarious; and suddenly this light bulb went off in my brain – these guys made movies for a living. It made me think I could actually pursue filmmaking as a career.

Gregg: What was your first film project?

Carlton: Following the adage of “write what you know” I teamed up with a Harvard classmate of mine to make a documentary about rowing. When it was done, we showed it to George Plimpton, who loved it and agreed to narrate it.

Gregg: So this was your calling card to break into the film business?

Carlton: Yes. I headed for Hollywood and used my film to get a job as the assistant to the head of one of the film studios. I drove him around in his car, ran errands and did his phone calls. After that, I got a job working as a reader for a film producer. I sat in an office, read and wrote coverage on over 350 scripts in the course of a year. I learned a lot about screenwriting by reading all those screenplays and the experience emboldened me to start writing myself. I would go home and write at night motivated by the story of Larry Kasdan who as the legend goes, wrote seven unproduced scripts before The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Body Heat, and The Big Chill in short succession.

Gregg: What was the first feature film you worked on?

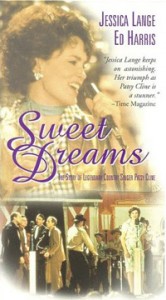

Carlton: I took a job working for producer Bernard Schwartz and spent a year and a half working on Sweet Dreams directed by Karel Reisz, starring Jessica Lange and Ed Harris. I spent months on location in West Virginia and Nashville, and I learned what it took to make a feature film from start to finish.

Gregg: This is when you started to figure out how things work?

Carlton: Yeah, it was my version of film school.

Gregg: What did you do next?

Carlton: Shorty after Sweet Dreams I got my first job as a writer on the Michael Mann series Crime Story, a crime drama, initially set in the 60s in Chicago. I got the job because I had helped a writer who was a good friend of mine named David Burke shape a script he was working on into final form. Michael Mann read that script and hired David to write the pilot of Crime Story. Once the show was ordered by NBC, David then turned around and hired me as a writer on the show. I wrote a couple of episodes. Michael Mann was busy working on a couple of features, and his two TV shows, Miami Vice and Crime Story all at the same time. He was a very talented, imposing and strong-willed guy.

Gregg: Crime Story started out in Chicago in 1963 and ended up in Las Vegas in 1980. How did that happen?

Carlton: There was an elaborate bible for Crime Story, but by episode three the show had already veered off in its own direction. I learned the profound lesson that TV series are their own organic entities that quickly take on a life of their own.

Gregg: What is the high point of your early career?

Carlton: I discovered early on that one thing I was very good at was picking writers. When I was working with Bernard Schwartz I was working on projects with yet-to-emerge writers like Gary Ross and Jeffrey Boam. Later on as a showrunner I gave first or very early jobs to writers like Shawn Ryan, Al Gough & Miles Millar, Russel Friend & Garrett Lerner, John McNamara, Pam Veasey, Glen Mazarra, Janet Tamaro, Josh Applebaum & Andrew Nemec, and, of course, Damon Lindelof. Everybody on this list went on to become showrunners themselves.

Gregg: Many of these relationships have come back around in your own career.

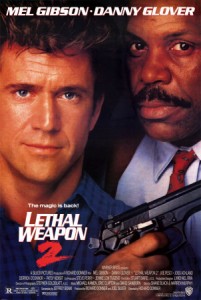

Carlton: Yes. After Crime Story, I was approached by Jeffrey Boam, who asked me to partner up with him. Jeffrey had just written Innerspace and Lost Boys for Warner Bros. and the studio was anxious to make a deal with us to develop, write and produce original movies. So we did.

Gregg: What happened? Did you make any movies?

Carlton: Right as we became partners, Jeffrey got the assignment to write Lethal Weapon 2. Our aspirations to create and write our own movies were suddenly sidelined as we were diverted into this franchise. I ended up spending a huge chunk of my time for the next five years helping to develop the stories and scripts for Lethal Weapon 2, Lethal Weapon 3 and then Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Gregg: That’s a long time to wait to do your own thing.

Carlton: That’s the power of franchise movies. They pay for everything else. So the studio definitely wanted all our energies focused there.

Gregg: Did you feel creatively inhibited?

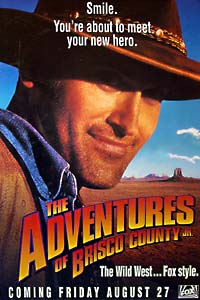

Carlton: Not at all. I poured a lot of my creative juices into those movies. And I really enjoyed working with Jeffrey. Then because of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade an executive at Fox, Bob Greenblatt, approached us and asked if we would be interested in doing a version of the old movie serials, like Indy, for TV. I really wanted to get back into TV so I came up with this idea – at first just an intriguing title– “The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.”, about a Harvard educated bounty hunter who returns to the old west to avenge the death of his father, who was the most famous lawman in the old West. But doing a straight western didn’t seem fresh enough, so we added this whole science fiction serial element to The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr., centered on this mysterious orb that conferred special powers to those who possessed it. Fox loved it ordered it to series. But Jeffrey decided he wanted to go back to the feature world. We split up and he went off to Paramount to write the movie, The Phantom, and I stayed at Warner Bros. and was the sole show runner for Brisco — and that really started my television career. Sadly, Jeffrey died a few years later.

Gregg: Brisco was your first time as a showrunner.

Carlton: Yes. I was learning on the job. Fortunately, one of my mentors was a writer and producer named John Sacret Young, who had co-created and was running a show called China Beach also for Warner Bros. His office was nearby on the lot, and we were working on a couple of projects together. I would go over to John’s office and hang out. I learned an enormous amount about showrunning from watching how John worked. His number two on that show was a super talented writer/producer named John Wells, who went on become the showrunner of both ER and The West Wing

.

Gregg: So was it difficult to transition from writer to showrunner?

Carlton: It was hard! Not only was I learning how to be a showrunner on the fly, we were also making the episodes for virtually no money on a seven day schedule. That was really tight to write scripts and shoot a show as ambitious as Brisco. But it ended up being one of the best experiences of my entire career because there was this incredible camaraderie among everyone working on the show. It all started with Bruce Campbell, our tireless and amazing star. His gung-ho attitude set a great tone on the set. He was always up for anything — from rain at 5 am to getting stampeded by cattle for 10 takes in a row.

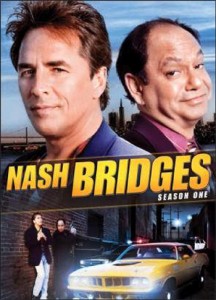

Gregg: Next was Nash Bridges. How did you get Don Johnson interested in the project?

Carlton: After Brisco I was offered the chance to take a meeting with Don. I was a huge fan of Miami Vice, so I thought it would be a kick to meet him. Vice was this very dark and nihilistic show, so I was surprised to find out that Don was actually a really charming and funny guy. He had a commitment from CBS to make a new series. He’d gone through a lot of writers and scripts without success. Once I met him I had this idea that I could create a show that would really show off his charming side. I told Don I’d go off and write a script and then when I was done he could decide whether he wanted to do it or not. I rode around with the San Francisco PD doing research; then I went off and wrote the pilot for Nash Bridges. When I was done I gave it to Don, he loved it, so we gave it to CBS and they ordered 14 episodes right off the script, without even making a pilot. In fact, Nash Bridges, was the first series that Les Moonves greenlit as the head of CBS. It ended up running for six seasons and 121 episodes.

Gregg: Six years is an incredibly long run. Almost no shows make it that long. What do you have to do to accomplish that?

Carlton: It sounds simple: You have to tell good stories. But it’s very hard to actually do that – to crank out a really solid script every eight days, which is the average time frame you have to write an episode for a series. On Nash the stories may have been light and fun in their construction, but we put a ton of work into them. It may seem like it’s easier to write comedic drama than heavy drama, but I promise you, it’s not.

Gregg: Now sometime during the middle of Nash Bridges you found time to create Martial Law?

Carlton: Yeah, during the 3rd season of Nash Bridges, Les Moonves approached me and said he was interested in doing a Hong Kong style martial arts series for TV. I thought it was a cool idea. I was a big fan of genre, and I’d always wanted to do something in the style of Jackie Chan’s Hong Kong films. This was before Rush Hour – before Jackie Chan was widely known to American audiences.

I thought it would be cool to marry the world of Hong Kong cinema to American television, so I came up with this story about a Shanghai cop who comes to the LAPD on an exchange program. We then hired a team of eight top Chinese stuntmen and coordinators out of Hong Kong, most of whom spoke no English. Stanley Tong, who had directed many of Jackie Chan’s biggest Hong Kong features, signed on to direct the pilot. And we cast Sammo Hung, one of Jackie Chan’s closest friends and collaborators, to star. And Sammo became the first Chinese actor to ever star as the lead in an American TV series.

Martial Law was one of only two shows out of ten new shows that debuted that year on CBS that was renewed for a second season. We won the TV Guide Award for Favorite New Series (1999).

Gregg: So were you doing two shows at once?

Carlton: Yeah. It was a totally insane year. I ran both Martial Law and Nash Bridges simultaneously. Between the two shows I made 46 hours of television that year. I never saw my family. It was too much.

So at the end of the season when both Nash and Martial Law were renewed, I decided I needed to make a change. I wanted to be more creatively focused and have a more manageable workload. I also had creative differences with Sammo Hung about the future direction of the show. So given all that, I thought the best plan was to step back from Martial Law and focus on Nash Bridges, which is what I did. Some other show runners came in to run Martial Law for the second season.

Gregg: But your next project was another martial arts show…

Carlton: Black Sash, a show about a San Francisco cop played by Russell Wong framed for a crime and sent to prison. He gets out and returns to San Francisco and opens a martial arts dojo for troubled but very attractive teenagers. It was not a show I created, I was simply a hired gun asked to come in and help get the show up on its feet. I think everyone involved made a noble effort, but at the end of the day it just wasn’t a TV show that worked. Most don’t! But the talented young writers on the show, Eddy Kitsis and Adam Horowitz, were the first new writers we hired onLOST. Also, we used a martial arts form on Black Sash called Ba-Gua. I loved the Chinese symbol for Ba-Gua, and so we took that symbol and it became the Dharma Symbol forLOST.

Gregg: Two martial arts shows in a row, weren’t you worried about being typecast?

Carlton: It happens to everybody. After Martial Law and Black Sash, I was the go-to martial arts guy. While I happened to like the genre, it was just one of many different genres of film that I liked. After those two shows I turned down everything having to do with martial arts. I wanted to move on and exercise different writing muscles.

Gregg: What was the genesis of your involvement with LOST?

Carlton: It started in the 6th season of Nash Bridges. I hired a writer named Damon Lindelof, who was just starting out his career, and gave him his first staff writer job on a TV series. After Nash ended, we stayed good friends. A few years later Damon got the job, along with JJ Abrams, to write the pilot for LOST.

Shortly after the LOST pilot was shot, JJ Abrams left the show to do Mission Impossible 3 with Tom Cruise. Damon was a wonderful writer but had no show running experience, so he started calling me and asking showrunning advice on the side. He sent me a rough cut of the pilot and some early scripts, and the more time I spent talking to him about the show, the more I fell in love with the material. My brain was completely activated.

Damon asked me if there was any way I could come over and work on the show. My agent was able to get me out of a deal I had at another studio, so I went to work on LOST.

Gregg: Wasn’t that a gamble? Did you seriously think LOST had a shot?

Carlton: Yes, I did. At the time literally no one believed LOST would work as a series except Lloyd Braun, the head of ABC who ordered the pilot and was subsequently fired. But I believed. In my head and in my heart, the story had enormous potential regardless of what everyone else was saying.

Gregg: What made you and Damon click so well?

Carlton: We saw LOST exactly the same way. We shared the same aesthetic. We pushed each other constantly to make it better.

Gregg: Most people are familiar with film where the director shapes the direction, but on TV it’s the showrunner.

Carlton: Exactly. The showrunner is the final creative decision maker.

Gregg: I noticed you guys wrote together most of the time. How did you split your duties?

Carlton: Occasionally we would divide and conquer — split up and do different things — but most of the time we did everything together. I think we wrote 35 or 36 hours of the show together, did all the re-writing together, story meetings, editing, casting — everything. There is so much work to be done in making a TV series. Having a partner, someone you can bounce ideas off of, someone to work with to build those ideas into even cooler ideas, and someone to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with you to defend the vision of the show – these are all reasons a great partnership can lead to great TV. In the case of LOST it worked out great; I could not have had a better partner.

Gregg: For you personally, what was LOST about?

Carlton: On the surface, LOST was a show about a group of people who survive a plane crash and find themselves lost on a mysterious island. But much more importantly, it was a show about how these people were metaphorically lost in their lives and searching for redemption. Viewers talked a lot about the mythology but for us making the show, it was always first and foremost about the characters.

Gregg: Did you do any other projects during LOST?

Carlton: LOST was my singular consuming creative focus for six years. I lived, breathed and even dreamed about the show. But for the show to be successful it required that kind of total emersion.

Gregg: Early on, did you feel like you were doing something special, something that had never been done before?

Carlton: Absolutely. Internally we all thought we were onto something cool. We were shattering a lot of the commonly held beliefs about what you could or couldn’t do on TV and that was an exciting feeling. Of course at that point, no one else believed the show would work as a series, so we talked a lot about how if the show did bomb after the 12 episode initial order, it would hopefully become a cool classic like Twin Peaks, which ran for 30 episodes — or The Prisoner, which ran for 17. We hoped, worse case scenario, that LOST would be the kind of show that gets passed around from geek to geek with people saying, “Hey, have you ever seen this show LOST?”

So with the idea that failure was okay, Damon and I asked ourselves one fundamental question to start: If someone handed us the DVD of the 12 episodes of LOST what would we want it to look like? We decided we’d make a show that the two of us thought would be cool.

Gregg: And you ended up breaking a lot of the traditional rules of narrative in TV.

Carlton: Yes. We did. We showed that it was possible on network TV to tell a highly complex, serialized narrative with intentional ambiguity — leaving the audiences room to debate and discuss the meaning and intentions of the narrative – and still find a large audience. This made it a game-changer, in my opinion.

Carlton: LOST came along at exactly the same time as the advent of social media on the Internet. There was a tremendous confluence between these two events. Huge virtual communities sprung up around the show and new media technology allowed fans to interact with each other and form a community around the show. The rise of social media allowed people around the world to not only debate and discuss the show but also work together and pool their resources to create content like Lostpedia, a massive, detailed and entirely fan-created encyclopedia about the show. This two-way interaction with a TV show was a brand new phenomenon. And the engagement with the audience occurred at a depth and on a scale that had never happened with a TV show before LOST. For example, we also created Lost University. Viewers who bought Blurays could take courses at Lost U. on LOST related subjects like time travel and Lost fans who become experts became the instructors of those courses.

Gregg: How did the role of showrunner change from Nash Bridges to LOST?

Carlton: When I started my career as a showrunner the job was just to write, produce and oversee a TV show. Now the job has expanded to being a brand manager, overseeing all the content created under the moniker of the show.

Gregg: How does transmedia storytelling figure into LOST?

Carlton: When we started the show the term transmedia didn’t even exist. We were making “transmedia” before anybody even knew what to call it.

While we always kept our primary focus on the network TV show, the mothership, as we called it, we creatively brainstormed and oversaw all the new media extensions. We wanted to see if we could use other platforms to tell stories that would never make it onto the network show. We started out by creating the first ARG (Alternative Reality Game) that connected as a narrative into a network TV show. This ARG redefined the way in which the Internet and a TV show could be integrated, and the ARG also broke new ground in how a TV show could be marketed. We were also the first TV network series show to create original content for mobile phones. Our last ARG, “Dharma Wants You” created an entire functioning, virtual community – a branch of the Dharma Initiative. That ARG was really cool and in my opinion pushed the boundaries of the transmedia envelope. It also ended up winning us an Emmy in 2009 for Creative Achievement in Interactive Media.

Gregg: Most showrunners are anonymous, not you and Damon!

Carlton: That’s right. Damon and I became the public face of LOST in a way that no other showrunners had been before us. We hosted a LOST podcast where we discussed the show that was regularly the #1 podcast on all of iTunes. We shot a whole series of comedic videos sponsored by Verizon called LOST Slapdown, and we were guests on shows like Jimmy Kimmel Live and The Letterman Show. We did a New York Times Talk that was simulcast in over 400 theaters in the US and Canada. Honesty, it was crazy on some level.Gregg: What was the importance of doing all this new media stuff for you?

Carlton: For me, it wasn’t about the money, it was about getting a chance to be a pioneer in this new media space. I knew we were the first ones out there engaging an audience simultaneously on multiple platforms with a TV show. I was fascinated with this shift in the TV paradigm and wanted to explore it.

Gregg: This new media also meant having to figure out new ways to do things, right? Like creating new labor agreements.

Carlton: Yeah. Somewhere around the third season of the show, the studio approached us and asked us to make some mobisodes – some mini episodes of LOST for the web and/or cellphones. The studio wanted to do them non-union. We refused.

We said if we were going to do the mobisodes they needed to be covered by Hollywood union agreements. We wanted our writers to write them and our directors to direct them and our main actors to be in them. They kept asking and we kept saying no, until finally they said, okay, we’ll work out a deal with all the unions.

Gregg: You got involved in the process, big time…

Carlton: Heavily. But mostly I give enormous credit to then ABC head, Mark Pedowitz, who literally moved mountains within the ABC/Disney culture to make it happen. In the end we made the very first new media deal of any kind with Hollywood Guilds – the WGA, DGA, and SAG. And it turned out to be a very fair deal for both sides.

Gregg: Is there a lasting impact of this deal you struck?

Carlton: Yes. The LOST deal became an important template for the first new media deals that were negotiated into the guilds overall agreements with the AMPTP. I was a member of the WGA Negotiating Committee, and helped in this process as well. It was of critical importance to establish that writers had the rights to residuals in new media. I think the concessions we won will be a very important source of income for future generations of writers.

Gregg: It’s been five months since the last episode of LOST aired, and with a little distance from that finale, how does it feel? Can you really let go?

Gregg: It’s been five months since the last episode of LOST aired, and with a little distance from that finale, how does it feel? Can you really let go?

Carlton: Absolutely. No tears. We got a chance to end our show on our own terms. That is a rare event in television. No show before us ever negotiated an end date to a series three years out. We told the story we wanted to tell, from beginning to end. Most TV shows are like horses in the Pony Express. You ride them until they drop dead underneath you. That didn’t happen to us. We rode our horses all the way into the stable. As for the finale, I’m proud of it. When I think back on it now, the ability to wrap up a show as complex and mythologically dense as LOST after six years was an almost impossible task. Added to that, were all the pressures and expectations because the show was still in the popular zeitgeist. And what I’m hearing now, 5 months out, is that most people really liked it. They were satisfied with the finale and with their experience of watching the show. To achieve a communion with your audience is the goal of all story telling. I feel like we did that for the vast majority of the viewers of LOST, and that makes me feel like it is possible to let go.

Gregg: But don’t you say to yourself: how do I top LOST?

Carlton: No. That would be paralyzing. It’s my goal to write and produce shows that engage me personally and feel different than other stuff on TV. I don’t want to make the 7th carbon copy of a law show or doctor show. I love smart and entertaining television; I hope to make some more shows that fit into that category.

Gregg: What are your plans for the near future?

Carlton: I’m working on some new projects. It’s a little too early to say anything specific about them. In the meantime, I’m doing a lot of reading and film watching. I’m also a member of TED, and I’ve been catching up on all the TED talks I missed while making LOST. They’re fascinating and often inspiring. Right now it’s all about recharging my creative batteries after six years of focusing on just one thing.

Whatever happens next in my career will be an exciting challenge. The great thing about this business is that every new project is a learning experience. I remember this quote by Akira Kurosawa who said at age 72 that he thought he was only now starting to figure out how to make films.

I completely get it. ♦

Be the first to comment